OTTAWA — The Public Order Emergency Commission has made 56 recommendations after investigating the federal government's use of the Emergencies Act to quell protests at border crossings and in downtown Ottawa in early 2022.

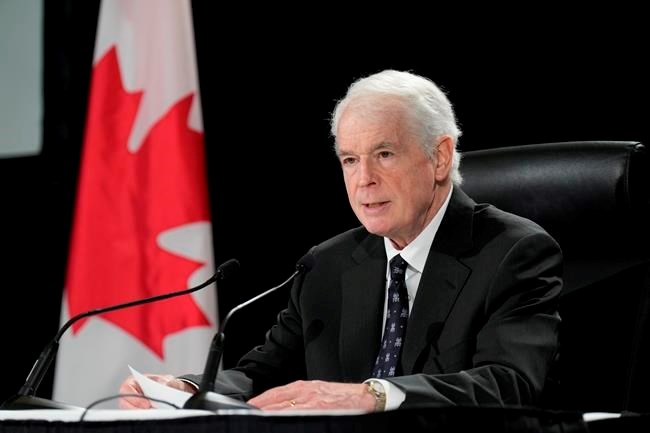

A number of Justice Paul Rouleau's recommendations are meant to address issues that arose during the public inquiry itself.

The federal government must do a better job of collecting and sharing information

The Liberal government has been criticized over the last year for not sharing enough information with the public, and with the inquiry, about its decision to invoke the Emergencies Act.

Opposition parties, the Canadian Civil Liberties Association and lawyers representing residents of Ottawa at the inquiry all complained that the government submitted thousands of pages of documents slowly throughout the inquiry, meaning it was difficult for them to review in time to question witnesses.

Many government documents were heavily redacted, and critical evidence — the legal opinion provided to cabinet to justify the use of the Emergencies Act — was never provided at all.

Rouleau's recommendations include the following obligations for future governments:

— Elected officials, staff and public servants should have to create a thorough written record of the process leading to a decision to declare an emergency, and should begin collecting those documents as soon as the decision is made.

— Governments should have to give the commission a "comprehensive statement setting out the factual and legal basis for the declaration and measures adopted, including the view of the Minister of Justice of Canada as to whether the decision … was consistent with the purposes and provisions of the Emergencies Act, and whether the measures taken under the act were necessary and consistent with the Charter."

— Government documents and information should not be redacted "on account of irrelevance, or on account of national security confidentiality and similar public interest privileges."

— Governments should be bound to produce all information, advice, and recommendations given to cabinet and its committees or ministers.

Clearer direction is needed for future inquiries

Rouleau's report acknowledges that he was not explicitly required to determine whether the government's decision to invoke the act was actually justified. The order-in-council tasked him with examining the circumstances leading to the decision and the effectiveness and appropriateness of the measures taken.

In the future, Rouleau said the Emergencies Act should be amended to provide greater clarity:

— That inquiries are called pursuant to Part 1 of the Inquiries Act, bringing it into line with other commissions of inquiry.

— Commissions should be given clear direction and "at a minimum, direct it to examine and assess the basis for the declaration and the measures adopted."

— The person chosen to lead the commission should be consulted on what is in the inquiry's terms of reference.

Officials from all levels of government should take part

Ontario Premier Doug Ford and the province's former solicitor general, Sylvia Jones, were notable absences from the list of witnesses at the hearings.

In fact, as the inquiry went on, lawyers for the Public Order Emergency Commission filed a subpoena to compel Ford and Jones to take the stand. But the pair successfully argued in court that they should not have to take part due to their parliamentary privilege as members of the legislature.

Rouleau recommends changes to the Emergencies Act that ensure:

— The commissioner can appoint someone to have jurisdiction to resolve claims of privilege.

— A federal parliamentarian "may not claim" privilege to refuse testifying.

— Commissioners should have the power to order a person to produce "any information, document, or thing under the person's power or control."

Future inquiries should be given more time

The public inquiry was under significant time constraints.

The Emergencies Act requires that a report be produced within 360 days of the emergency declaration being revoked (that happened on Feb. 23, 2022). But Rouleau was not named as commissioner of the inquiry until April 25, 2022, giving him even less time to come up with a final report.

He recommends changing that so the 360 days begins when the order-in-council is made to create the commission.

Rouleau also said future commissioners should have the power to extend the time to produce the report by up to six months.

There should be accountability

The government is not compelled to implement any of the commission's recommendations.

Rouleau recommends the following accountability measures:

— Within 12 months, the government should publicly say which recommendations it accepts and which it rejects, with "detailed explanations" for why they are rejected.

— The government should also provide a timeline for when those recommendations will be implemented.

— Parliament should create an implementation committee for those recommendations.

This report by The Canadian Press was first published Feb. 17, 2023.

David Fraser, The Canadian Press